Google has recently released SearchWiki, a set of tools for annotating Google search results. It's a rather dramatic change to the main search page, accesible by anyone logged into a Google account.

The interesting thing is that it seems like a personal version of Wikia Search (personal in the sense that only your alterations change the order of results, although you can see comments from everyone), though earlier comparisons were made more to link sharing sites like Digg.

So, might the emergence of this tool mean that Google is not, unlike so many others, underestimating the potential of Wikia Search?

Tuesday, 25 November 2008

The human touch

Posted by

Stephen

at

12:47 am

0

comments

![]()

Tuesday, 18 November 2008

Bug statistics

Since the beginning of September, the bug tracker for MediaWiki has been sending weekly updates to the Wikitech-l mailing list, with stats on how many bugs were opened and resolved, the type of resolution, and the top five resolvers for that week. With eleven weeks of data so far, some observations can be made.

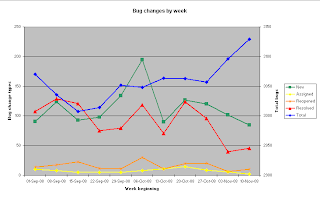

The following graph shows the number of new, resolved, reopened and assigned bugs per week (dates given are the starting date for the week). The total number of bugs open that week is shown in blue, and uses the scale to the right of the graph:

The total number of open bugs has been trending upwards, but only marginally, over the past couple of months. It will be interesting to see, with further weekly data, where this trend goes.

It also seems that the number of bugs resolved in any given week tends to go up and down in tandem with the number of new bugs reported in that week. Although there is no data currently available on how quickly bugs are resolved, I would speculate that most of the "urgent" bugs are resolved within the week that they are reported, which would explain the correlation.

Note also the spike in activity in the week beginning 6th October; this was probably the result of the first Bug Monday.

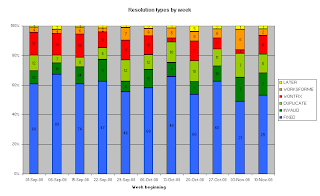

The second graph shows the breakdown of types of bug resolutions:

The distribution seems fairly similar week on week, with most resolutions being fixes. It's interesting to note that regularly around 25% to 35% of bug reports are problematic in some way, whether duplicates or bugs that cannot be reproduced by testers.

The weekly reports are just a taste of the information available about current bugs; see the reports and charts page for much more statistic-y goodness. And kudos to the developers who steadily work away each week to handle bugs!

Posted by

Stephen

at

7:08 pm

1 comments

![]()

Labels: bugs, MediaWiki, statistics

Sunday, 31 August 2008

How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies and Nations (and Wikipedia articles)

Alaska Governor Sarah Palin was selected as presumptive Republican presidential candidate John McCain's running mate on Friday, and her Wikipedia article has seen a predictable explosion in editing activity. From the article's creation in 2005, up until the announcement on Friday, the article had been edited something like 900 times. Since then, however, it's been edited nearly 2000 times again.

What's more interesting is how the article was edited before the announcement was made. Ben Yates mentions this NPR story detailing edits made to the page by a user called Young Trigg, who may or may not have been Palin herself (or someone on her staff). But Young Trigg was not the only person editing the article.

The Washington Post reports on some analysis done by "Internet monitoring" company Cyveillance, which found that Palin's article was edited more heavily in the days leading up to the announcement than any of the articles on the other prospects for the nomination. A similar pattern emerged in relation to the articles on the frontrunners for the Democratic vice-presidential nomination: Joe Biden's article was edited more heavily than the other potential picks in the leadup to his selection as Obama's running mate last week.

Also similar were the types of edits being made: both Palin and Biden's articles saw many footnoting and other accuracy-type edits in the leadup to the announcements of their selection. As a final piece of intrigue, the editors making these edits about Palin and Biden were far more likely to also be actively editing McCain and Obama's articles respectively than were the editors editing articles on the other potential nominees.

There are at least two explanations for these patterns. The first is that the two campaigns, knowing full well who the nominees would be, were editing the articles in advance of the announcement to ensure that they were accurate (or to take the cynical view, to ensure that they were favourable), knowing full well that Wikipedia would be one of the major sources of information for the public - and for journalists and campaign staff too - following the announcements.

The alternative is more interesting, to my mind. Cyveillance, who did the analysis, is usually in the business of data mining in the business world, aiming to collate disparate sources of public information to predict financial and commercial events before they are publicly announced. Wikipedia may be performing exactly the same function: a variety of editors collating disparate pieces of information in a far more powerful way than any individual could. It's already (un)conventional wisdom that the betting markets are equal or better predictors of elections than opinion polls are: a basic application of the efficient market hypothesis. In a similar way, high profile, highly edited Wikipedia articles like these are the marketplace of the information economy.

Posted by

Stephen

at

2:18 pm

0

comments

![]()

Labels: information economy, Wikipedia

Saturday, 23 August 2008

Userpage Google envy

Brianna Goldberg, a Canadian journalist with the National Post, wrote on Friday about her efforts to become the number one Google result for her name. Her quest was sparked by discovering that the Wikipedia user page of another Brianna Goldberg was ensconced in the top spot.

The journalist Goldberg obtained advice from search engine optimization experts on methods for advancing her ranking, but still had difficulty displacing the userpage. Moreover, the article on the journalist comes in second to the userpage in results from Wikipedia. Wikipedia user pages are certainly highly visible: every time you sign an edit, you're creating a link to your user page.

This relates to a discussion from last month on the mailing list about whether user pages (and certain other types of pages) should be indexed by search engines at all. The Wikimedia sites already instruct search engines not to crawl certain pages, including deletion debates, requests for arbitration pages and requests for adminship, but there have regularly been calls for more types of pages to be restricted (see here for example).

So, should user pages be blocked from search engine crawlers?

Posted by

Stephen

at

4:35 pm

4

comments

![]()

Labels: Wikipedia

Monday, 18 August 2008

US court groks free content licensing

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit handed down an interesting and significant decision on Wednesday, which could have a number of valuable implications for the validity of free content licences.

The case, Jacobsen v Katzer, was about software for interfacing with model trains. Robert Jacobsen is the leader of the Java Model Railroad Interface project (JMRI), which releases its work under the Artistic License 1.0; Matthew Katzer (and his company Kamind Associates) produce commercial model train software products. It was alleged that either Katzer or another employee of Kamind took parts of the JMRI code and incorporated it into its own software, without identifying the original authors of the code, including the original copyright notices, identifying the JMRI project as the source of the code, or indicating how it had modified the original JMRI code.

Jacobsen sought an interlocutory injunction, arguing that since Katzer and Kamind had breached the Artistic License, their use of the JMRI code constituted copyright infringement. However, the District Court considered that Jacobsen only had a cause of action for breach of contract, not for copyright infringement, and because of this Jacobsen could not satisfy the irreparable harm test (in the case of copyright infringement, irreparable harm is presumed in the 9th Circuit), and was not entitled to an injunction.

Jacobsen's appeal to the Court of Appeals was against this preliminary finding. An assortment of free content bodies (including Creative Commons and the Wikimedia Foundation) appeared as amici curiae in the case, submitting an interesting brief containing a number of arguments that the Court of Appeals seemed to agree with.

The legal issue at stake in the appeal concerned the difference between conditions of a contract and ordinary promises (covenants, in US parlance). If a term in a contract is a condition, then the promisee has a right to terminate the contract. In the context of a copyright licence, if someone using the licensed material breaches a condition of the licence, they are then open to a copyright infringement action (unless they have some other legal basis for using the material). Contract law will still hold someone responsible for breaching a contractual promise, but the remedies are different, and as was the issue here, it's much harder to get an interlocutory injunction.

Whether or not a term is a condition is a matter of construction, and depends on the intention of the parties. In answering the question of whether the relevant terms were conditions, the Court of Appeals made a number of important observations which are applicable to free content licences generally.

The first observation was that, just because with free content licensing there is no money changing hands, it is not the case that there can be no economic consideration involved. The Court recognised several other forms of economic benefit which free content licensors derive from licensing their works:

"There are substantial benefits, including economic benefits, to the creation and distribution of copyrighted works under public licenses that range far beyond traditional license royalties. For example, program creators may generate market share for their programs by providing certain components free of charge. Similarly, a programmer or company may increase its national or international reputation by incubating open source projects."

This is a really significant observation for the court to make, because there are some major ideological barriers that seemed to get in the way of the District Court on this point. Even though free content licencing is all about authors dealing with their economic rights under copyright, free content is all too often viewed as non-economic. Just because free content doesn't fit in with the traditional royalties-based system, it does not mean that there are not real economic motives involved.

The second observation was made in the context of the general rule (applicable in that jurisdiction) that an author who grants a non-exclusive licence effectively waives their right to sue for copyright infringement. If the relevant terms were conditions, then they would be capable of serving as limitations on the scope of the licence, which would negate this rule. The Court said that:

"[t]he choice to exact consideration in the form of compliance with the open source requirements of disclosure and explanation of changes, rather than as a dollar-denominated fee, is entitled to no less legal recognition."

Again, this seems to be an important point in terms of getting over psychological hurdles. The District Court was clearly hung up on the terms in the Artistic License allowing users to freely distribute and modify licensed material; it focused on the breadth of the freedoms granted. In doing so it overlooked that while the License did grant broad freedoms, it clearly circumscribed them. The Court of Appeals understood what the District Court did not: that releasing material under a free licence is not the same as giving it away.

The heart of the decision was of course about the particular wording in the Artistic License. The use of the phrase "provided that" in the Artistic License was significant, because such wording usually indicates a condition under Californian contract law. Further, the requirement that any copies distributed be accompanied by the original copyright notice - a relatively common term - also typically indicates a condition.

In the end, the Court of Appeals decided that the relevant terms were conditions, and that Jacobsen had a copyright infringement action open to him. Since the District Court didn't assess Jacobsen's prospects of success on the merits, the Court of Appeals remanded the injunction application back to them for their consideration. Given that Katzer and Kamind apparently conceded that they did not comply with the Artistic License, Jacobsen would seem a good chance to get his injunction, and later to succeed at the merits stage.

Though much turned on the particular wording here, the reasoning behind the assessment of the terms can easily be applied to other free content licences, as can the recognition of the economic motives involved in free content licencing, motives which though non-traditional, are both legitimate and worthy of protection by the law. Independent of any value as a binding precedent, this case is a magnificent example of a court really appreciating the vibe of free content.

Posted by

Stephen

at

1:18 am

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Artistic License, free content, legal

Monday, 28 July 2008

Kno contest

Google's Knol was opened to the public last week, to much fanfare. When Knol was announced in December last year, it was immediately compared to Wikipedia, and the comparisons keep coming now that it has launched. However, as I wrote at the time, the comparison seemed to be wide of the mark in many important ways. Now that Knol has launched and we can see how it will actually work, I think the accuracy of the comparison is still not borne out.

The three key differences I noted at the time were the lack of collaboration in writing knols, the plurality of knols (more than one on the same subject) and that knols will not necessarily be free content, differences which go to the core of what makes Wikipedia what it is.

As it turns out, Knol does provide a couple of options for collaboration, allowing authors to moderate contributions from the public, or allow public contributions to go live immediately, wiki-style. The other mode is closed collaboration, but it does allow for multiple authors at the invitation of the original author.

As the sample knol hinted, Knol does provide for knols to be licensed under the CC-BY 3.0 licence by default, and allows authors to choose the CC-BY-NC 3.0 licence, or to reserve all rights to the content. However, these are the only licences available; in particular, no copyleft licences are available.

Of course, the thing to remember is that Knol is an author-oriented service, so even if an author selects open collaboration and the CC-BY licence, it appears that they can change their minds at any time, and, for example, close collaboration on a previously open knol (I might need to do some closer reading of the terms of service, but it would also appear possible to revert the Knol-published version to all rights reserved model, too).

The author-oriented approach is apparent in most of the features of Knol. On a knol's page you don't see links to similar knols, or knols on related topics (as you would on a Wikipedia article) you see links to knols written by the same author. Knols aren't arranged with any kind of information structure like Wikipedia categories, or even tags; the URLs are hierarchical, but there knols are gathered under the author's name.

No, Knol is not a competitor to Wikipedia (or at least, it's competing for a different market segment). It's more a companion to another Google property, Blogger. It's a publishing platform, but not for diary-style, in-the-moment transient posts; it's for posts that are meant to be a little more timeless, one-off affairs. Google say so at their Blogger Buzz blog:

"Blogs are great for quickly and easily getting your latest writing out to your readers, while knols are better for when you want to write an authoritative article on a single topic. The tone is more formal, and, while it's easy to update the content and keep it fresh, knols aren't designed for continuously posting new content or threading. Know how to fix a leaky toilet, but don't want to write a blog about fixing up your house? In that case, Knol is for you."

Some of the content on Knol might start off looking like Wikipedia articles, but over time I'll bet that the average "tone" of knols will find a middle ground between blogs and Wikipedia's "encyclopaedic" tone as people come to use Knol as a companion to blogging.

Posted by

Stephen

at

10:36 pm

1 comments

![]()

Monday, 2 June 2008

Rambot redux

FritzpollBot is a name you're likely to be hearing and seeing more of: it's a new bot designed to create an article on every single town or village in the world that currently lacks one, of which there are something like two million. The bot gained approval to operate last week, but there's currently a village pump discussion underway about it.

FritzpollBot has naturally elicited comparisons with rambot, one of the earliest bots to edit Wikipedia. Operated by Ram-Man, first under his own account and then under a dedicated account, rambot created stubs on tens of thousands of cities and towns in the United States starting in late 2002.

It's hard for people now to get a sense of what rambot did, but its effects even now can be seen. All told, rambot's work represented something close to a doubling of Wikipedia's size in a short space of time (the bulk of the work, more than 30,000 articles, being done over a week or so in October 2002). The noticeable bump that it produced in the total article count can still be seen in present graphs of Wikipedia's size. Back then the difference was huge. I didn't join the project until two years after rambot first operated, but even then around one in ten articles had been started by rambot, and one would run into them all the time.

During its peak, rambot was adding articles so fast that the growth rate per day achieved in October 2002 has never been outstripped, as can be seen from the graph below (courtesy Seattle Skier at Commons):

There was some concern about rambot's work at the time: see this discussion about rambot stubs clogging up the Special:Random system, for example. There were also many debates about the quality and content of the stubs, many of which contained very little information other than the name and location of the town.

The same arguments that were made against rambot at the time, mainly to do with the project's ability to maintain so many new articles all at once, are being made again with respect to FritzpollBot. In the long run, the concerns about rambot proved to be ill-founded, as the project didn't collapse, and most (if not all) of the articles have now been absorbed into the general corpus of articles. The value of its work was ultimately acknowledged, and now there are many bots performing similar tasks.

In addition to the literal value of rambot's contributions, there's a case to argue that the critical mass of content that rambot added kickstarted the long period of roughly exponential growth that Wikipedia enjoyed, lasting until around mid-2006. I don't think it's unreasonable to suggest that having articles on every city or town in the United States, even if many were just stubs, was a significant boon for attracting contributors. From late 2002 on, every American typing their hometown or their local area into their favourite search engine would start to turn up Wikipedia articles among the results, undoubtedly helping to attract new contributors. The stubs served as a base for redlinks, which in turn helped build the web and generate an imperative to create content. Repeating the process for the rest of the world, as FritzpollBot promises to do, would thus be an incredibly valuable step.

Furthermore, as David Gerard observes, when rambot finished its task the project had taken its first significant step towards completeness on a given topic. Rambot helped the project make its way out of infancy; now in adolescence, systemic bias is one of the major challenges it faces, and hopefully FritzpollBot can help existing efforts in this regard. Achieving global completeness across a topic area as significant as the very places that humans live would be a massive accomplishment for the project.

Let's see those Ws really cover the planet.

Posted by

Stephen

at

2:26 am

1 comments

![]()

Labels: bots, statistics, Wikipedia

Monday, 26 May 2008

Wikipedia to be studied in New South Wales from 2009

The Board of Studies in the Australian state of New South Wales, which sets the syllabus for high school students across the state, has included Wikipedia as one of the texts available for study in its "Global Village" English electives, according to The Age.

The new syllabus will apply from 2009-2012, and (certain selected parts of) Wikipedia will be one of four texts available in the elective. It will be up to teachers to choose which text is studied, so there are no guarantees that Wikipedia will actually be studied in New South Wales :) According to the syllabus documentation (DOC format), the other alternatives are the novel The Year of Living Dangerously, about the downfall of Sukarno and the rise of Suharto in Indonesia in 1965; the play A Man with Five Children; and the modern classic film The Castle.

I think formalised educational study of Wikipedia is going to be very important in the future, as the reality of its success and its widespread use coincides with a long period of neglect of skills in critically evaluating source material in many schools, certainly in this country. Thankfully the people at the Board of Studies seem to get this. There's also a good quote from Greg Black at the non-profit educational organisation education.au:

"The reality is that schools and schools systems are going to have to engage with this whether they like it or not... what the kids really need to learn about is whether it's fit for purpose, the context, the relevance, whether there's an alternative view - an understanding about how to use information in an effective way."

And, just for good measure The Age article features a quote from Privatemusings, exhorting students to "plug in". Indeed, some good advice.

Posted by

Stephen

at

12:07 pm

2

comments

![]()

Saturday, 26 April 2008

Citationschadenfreude

Oh dear. Queensland-based Griffith University has been copping flak over the past few days for asking the government of Saudi Arabia to contribute money towards its Islamic Research Unit, having previously accepted a smaller grant last year. One state judge branded the university "an agent of extreme Islam".

The university's vice-chancellor Ian O'Connor defended accepting the grant and seeking further money, but was today busted by The Australian newspaper for lifting parts of his defence from Wikipedia's article on Wahhabism. Worse, the change that was made to the copied text rendered it inaccurate. The irony that O'Connor had previously gone on the record recommending that Griffith students not use Wikipedia was not lost on the media.

The good news is that while there's been plenty of criticism from journalists and commentators of O'Connor, both for copying in the first place and then for introducing a pretty dumb mistake with his change, there've been no reported problems with the Wikipedia material O'Connor copied. Furthermore, the copy of O'Connor's response on the Griffith website now properly quotes and footnotes Wikipedia. Score one to us, I think :)

Posted by

Stephen

at

1:12 am

0

comments

![]()

Saturday, 29 March 2008

Wikipedia's downstream traffic

We've been hearing for a while about where Wikipedia's traffic comes from, but here are some new stats from Heather Hopkins at Hitwise on where traffic goes to after visiting Wikipedia. Hopkins had produced some similar stats back in October 2006, and it's interesting to compare the results.

Wikipedia gets plenty of traffic from Google (consistently around half) and indeed other search engines, but what's interesting is that nearly one in ten users go back to Google after visiting Wikipedia, making it the number one downstream destination. Yahoo! is also a popular post-Wikipedia destination.

It was nice to see that Wiktionary and the Wikimedia Commons both make it into the top twenty sites visited by users leaving Wikipedia.

Hopkins also presents a graph illustrating destinations broken down by Hitwise's categories. More than a third of outbound traffic is to sites in the "computers and internet" category, and around a fifth to sites in the "entertainment" category, which probably ties in with the demographics of Wikipedia readers, and the general popularity of pop culture, internet and computing articles on Wikipedia.

Hopkins makes another interesting point on the categories, that large portions of the traffic in each category are to "authority" sites:

"Among Entertainment websites, IMDB and YouTube are authorities. Among Shopping and Classifieds it's Amazon and eBay. Among Music websites it's All Music Guide For Sports it's ESPN. For Finance it's Yahoo! Finance. For Health & Medical it's WebMD and United States National Library of Medicine."

Similarly, Doug Caverly at WebProNews states that the substantial proportion of traffic returning to search engines after visiting Wikipedia "probably indicates that folks are continuing their research elsewhere", and this ties in well with Hopkins' observation about the strong representation of reference sites.

All of this suggests that Wikipedia is being used the way that it is really meant to be used: as a first reference, as a starting point for further research.

Posted by

Stephen

at

12:13 am

0

comments

![]()

Labels: statistics, Wikipedia

Monday, 17 March 2008

Protection and pageviews

Henrik's traffic statistics viewer, a visual interface to the raw data gathered by Domas Mituzas' wikistats page view counter, has generated plenty of interest among the Wikimedia community recently. Last week Kelly Martin, discussing the list of most viewed pages, wondered how many page views are of protected content; that thought piqued my interest, so I decided to dust off the old database and calculator and try to put a number to that question.

The data comes from the most viewed articles list covering the period from 1 February 2008 to 23 February 2008. I've used that data, and data on protection histories from the English Wikipedia site, to come up with some stats on page protection and page views. There are some limitations: I don't have gigabytes of bandwidth available, so some of the stats (on page views in particular) are estimates, and protection logs turn out to be pretty difficult to parse, so I've focused on collecting duration information rather than information on the type of protection (full protection, semi-protection etc). Maybe that could be the focus of a future study.

There were 9956 pages in the most viewed list for February 1 to February 23 2008. Excluding special pages, images and non-content pages, there were 9674 content pages (articles and portals) in the list. Interestingly, only 3617 of these pages have ever been protected, although each page that has been protected at least once has, on average, been under protection nearly three times.

Protection statistics

Only 1223 (12.6%, about an eighth) of the pages were edit protected at some point during the sample period, 902 of those for the entire period (a further 92 were move protected only at some point, 69 of those for the entire period). Each page that had some period of protection was protected for, on average, 82.9% of the time (just under 20 days), though if the pages protected for the whole period are excluded, the average period spent protected was only 34.8% of the time (just over eight days).

The following graph shows the distribution of the portion of the sample period that pages spent protected, rounded down to the nearest ten percent:

The shortest period of protection during the period was for Vicki Iseman, protected on 21 February by Stifle, who thought better of it and unprotected just 38 seconds later.

Among the most viewed list for February, the page that has been protected the longest is Swastika, which has been move protected continuously since 1 May 2005 (more than 1050 days). The page that has been edit protected the longest is Marilyn Manson (band), which has been semi-protected since 5 January 2006 (more than 800 days).

Interestingly, the average length of a period of edit protection across these articles (through their entire history) is around 46 days and 16 hours, whereas the average length of a period of move protection is lower, at 41 days 14 hours. I had expected the average bout of move protection to last longer, although almost all edit protections do include move protections.

The next graph shows the distribution of protection lengths across the history of these pages, for periods of protection up to 100 days in length (the full graph goes up to just over 800 days):

Note the large spikes in the distribution at seven and fourteen days, the smaller spike at twenty-one days and the bump from twenty-eight to thirty-one days, corresponding to protections of four weeks or one month duration (MediaWiki uses calendar months, so one month's protection starting January will be 31 days long, whereas one month's protection starting September will be 30 days long).

The final graph shows the average length of protection periods (orange) and the number of protection periods applied (green) in each month, over the last four years:

At least on these generally popular articles, protection got really popular towards the end of 2006 into the beginning of 2007, and again a year later. However, it seems that protection lengths peaked around the middle of 2007 and have been in decline since then.

Protection and pageviews

What really matters here though is the pageviews. The 9674 content pages in the most viewed list were viewed a total of 805,569,269 times over the relevant period. The 1223 pages that were edit protected for at least part of the period were viewed a total of 270,057,550 times (33.5%), with approximately 247 million of these pageviews coming while the pages were protected.

This is a really substantial number of pageviews, however, this number includes the Main Page, which alone accounts for more than 114 million of those pageviews. Leaving the Main Page out of the equation gives a healthier figure of around 133 million views to protected pages during the relevant period (and remember, this is only counting pages on the most viewed list).

Conclusions

Although only one in eight of the pages in the most viewed list were protected at some point during the relevant period, they tended to be higher-profile ones, accounting for one third of the page views. The pages that were protected at some point tended to be protected alot of the time, three-quarters of them for the entire sample period. This certainly fits with what many people have already suspected, that a small pool of high-profile articles attract plenty of attention in the form of both page protection and page views.

It will be interesting to do some more analysis on the history of page protection. Based on just this small sample, it seems that average protection lengths are trending downwards, which could well be something to do with the advent of timed protection. Hopefully I'll have some more insights to come.

Posted by

Stephen

at

1:13 am

1 comments

![]()

Labels: pageviews, protection, statistics, Wikipedia

Sunday, 16 March 2008

Today's lesson from social media

So much for claims that Jimmy Wales uses his influence to alter content for his friends: according to Facebook's Compare People application, Jimmy may be the best listener, the best scientist and the most fun to hang out with for a day, but he's nowhere to be seen in the list of people most likely to do a favour for me.

Posted by

Stephen

at

10:38 pm

0

comments

![]()

Wednesday, 20 February 2008

Beware corners

I'm sure that everyone who follows the news around Wikipedia will be aware of the latest controversy to gain attention in the media, namely the dispute about the inclusion of certain images in Wikipedia's article on Muhammad. Much of the external attention has focused on an online petition that calls for the removal of the images which, at the time of writing, has more than 200,000 signatures.

The debate so far has been understandably robust. Unfortunately, issues like these tend to harden positions, and push people towards the extremes. Consider a recent example: the seventeen Danish newspapers who, in the wake of the arrest of three men suspected of planning to assassinate Kurt Westergaard, author of one of the cartoons at the heart of the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy, republished the cartoons in retaliation.

Likewise, positions are being hardened in this debate among both supporters and opponents of the images. The relevant talk pages are remarkably free of comments (from either side) even contemplating compromise. The Foundation is receiving emails on the one hand giving ultimatums that the images be removed, and on the other exhorting the Foundation not to "give in" to "these muslims [sic]".

Retreating into corners like this is contrary to the ethos of Wikipedia, which operates on open discussion in pursuit of neutrality. So just as the supporters of the images are asking opponents to challenge their assumptions, so too should the supporters be prepared to challenge their own.

The first assumption that should be questioned is that the images are automatically of encyclopaedic value. Images have little value in an encyclopaedia unless used in a relevant context and given sufficient explanation. Take this image, for example. An interesting image, but unless it is explained that it appears in Rashid al-Din's 14th century history Jami al-Tawarikh, and the observation made that it is thought to be the earliest surviving depiction of Muhammad, it lacks its true significance. We have a whole article on depictions of Muhammad. While some of the images in it are discussed directly, many are merely presented in a gallery, without much text to indicate their importance or relevance.

The second assumption worth revisiting is the assumption that, since the images were created by Muslim artists, then there are no neutral point of view problems. This view overlooks the fact that there are many different traditions within Islam, not only religious ones but artistic ones also. The Almohads, for example, with their Berber and eventual Spanish influences, had vastly different cultural and artistic influences than the Mongol, Turkic and Persian influenced Timurids. The Fatimids of Mediterranean Africa had different influences again from the Kurdish Ayyubids.

The Commons gallery for Muhammad contains an abundance of medieval Persian and Ottoman depictions, a small handful of Western depictions, but only one calligraphic depiction, and no architectural ones. Calligraphy is extremely significant in Islamic art, given the primacy of classical Arabic as a liturgical language in all Islamic traditions. It's worth considering why there is such an over-representation of Persian and Ottoman works, and such a dearth of works from other Islamic traditions. It's worth considering for a moment whether the Western preference for natural representations, as opposed to the abstract representations preferred in most Islamic traditions, has informed the predominance of physical depictions of Muhammad in the English Wikipedia and on Commons.

These images should not be removed altogether; many come from historically significant works, and represent a significant artistic tradition. But the images - as with any other content on Wikipedia - ought to be used in appropriate and expected contexts, and ought not be used exclusively or primarily to illustrate these articles, but should be accompanied by images representative of other traditions.

Most of all, discussions on these questions should proceed openly and freely, and all participants should make an effort to question their assumptions, and move away from their corners.

Posted by

Stephen

at

3:13 am

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Muhammad images, neutral point of view, Wikipedia